News & Community

One participant wrote about a tree—later dubbed the “Survivor Tree”—and the incongruities between what survived and what didn’t, and what was supposed to protect people and what didn’t. Another participant made a sculpture out of objects from her daughter’s purse. The purse survived the bombing, but her daughter did not. In the days following the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, many Oklahoma nonprofits and organizations came together and found ways to help however they could.

The Oklahoma Arts Institute responded by creating the Celebration of the Spirit Workshops for those directly affected by the attack. In the fall of 1995, 140 survivors and family members of victims gathered at Quartz Mountain for four days of creating, expressing and healing. The culturally and historically significant works of art produced during these four days are now archived at the Oklahoma City National Museum & Memorial.

The impetus was a phone call from actress Jane Alexander, then chairperson of the National Endowment for the Arts, to then-Arts Institute President Mary Frates. Frates noted that shortly after the bombing, Alexander called and simply said, “Do something. I don’t know what, but the Arts Institute should do something. And when you do, we’re here to help.”

The NEA and the First Presbyterian Church of Oklahoma City provided the bulk of funding for the workshops. For the NEA, it was the first time the agency had ventured into funding art projects for survivors of tragedies. After the Celebration of the Spirit workshops, the NEA funded arts projects for children in New York City post-9/11, and workshops for veterans with PTSD.

The Arts Institute worked to ensure that anyone who wanted to attend would be accepted, but also that there would be no “dumbing down” of the workshops. The classes would be of the same caliber as our Fall Institute’s, held annually at Quartz Mountain, with nationally renowned artists and educators teaching.

Although the workshops were not designed to be “art therapy,” there was a mental health counselor in every class. The counselors participated alongside the survivors and their families, just in case their help and expertise were needed.

Frates could sense that the survivors and their family members who attended were happy in the environment at Quartz Mountain. “Every day, I could sense more communing, more joy. Although there were tears, there was a definite trajectory of positive emotion. It felt good. It felt right. It was working,” she wrote in her notes.

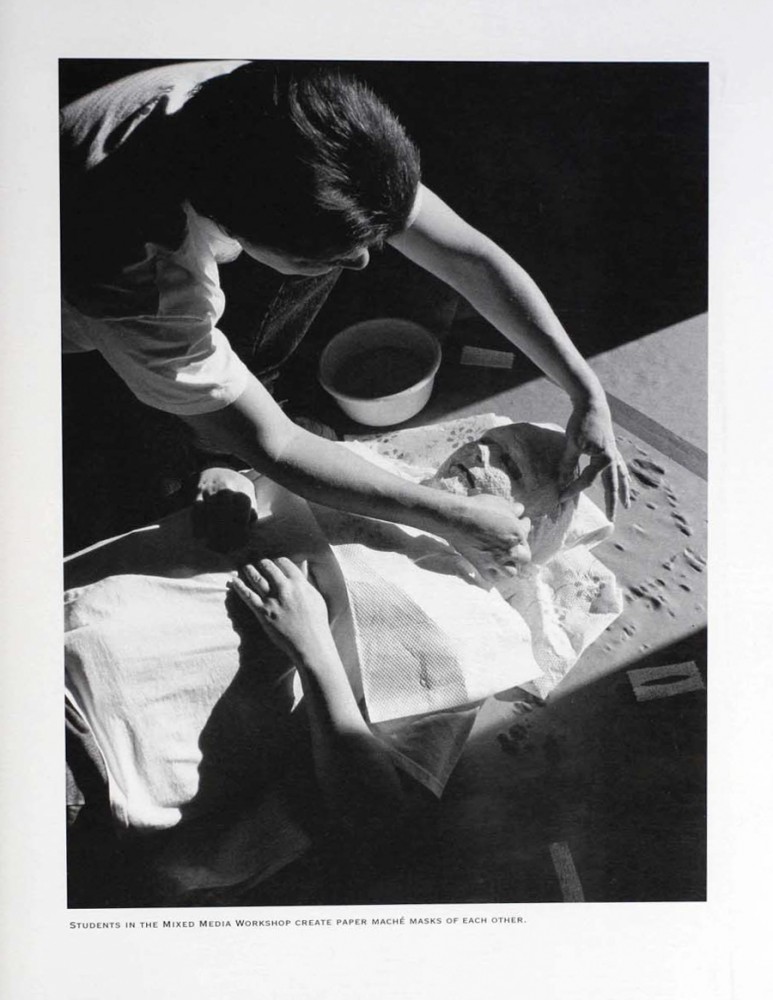

The focus of the program was to give survivors a space to create in whatever capacity they needed at that time. Participants studied personal essay, poetry, Cherokee basketmaking, memory box sculpture, mask making and mixed media. There were also workshops for children and teenagers, as well as gospel music sessions.

Barbara Williams, a participant from Cashion who had lost her husband in the bombing, wrote in her journal, “My poetry classmates and instructor have made me think, let me talk, and cry tears of joy instead of sadness. I came [to the workshop] to try to release some of my thoughts, to get them on paper, and to hear other peoples’ stories.”

Judith Kitchen, the author and poet who taught the personal essay workshop that weekend, said, “What happened in our wind-wracked trailer defie[d] description…our ‘stories’ were filled with compassion and understanding, with imagination and creativity, but most of all with an honesty that leap[t] from the page. That was the gift we gave each other: we were honest about our thoughts and feelings and aspirations. We acknowledged each other’s pain – and we moved on.”

With guidance from the workshop faculty, survivors—most of whom had never written poetry or created art—produced work that was raw and beautiful.

Poetry workshop participant Jody Collier wrote about the “Survivor Tree” that she and her co-workers would walk past every day:

Do you remember the tree on the corner between our buildings?

We all saw it. We all walked past it.

We walked past each other too. We didn’t look at each other but we all saw the tree. There it was on CNN! – on that little screen they showed it again and again…it stood there in the smoke. It grew out of the cement, nourished by the pavement, I suppose with leaves BLOWN AWAY!

It seemed so unimportant to the picture, but we all saw it.

Then on THAT day, when the buildings didn’t shelter us.

Frates wrote in her notes, “They worked hard, really hard. No one went fishing. Classes lasted longer and longer, and people worked in the studios into the night. The work was not only good; It was very good.”

In the memory sculpture workshop, Connie Ziegelgruber of Guthrie created “In the Woods, Without the Forest,” a sculpture of objects found in the hills surrounding Quartz Mountain. The objects—pieces of trees in various states of decomposition and leaves of different hues and shapes—are composed in a way that looks both chaotic and balanced.

“Each item has a very special meaning to me, and represents a particular time in my life,” Ziegelbruber wrote in her journal. “In the process of assembling my box, I found that in sharing work, laughter, and sometimes tears with our teacher and the people in my class, I was able to allow some long-buried feelings to surface.”

One of the participants in the mixed media workshop, Caren Cook, created a sculpture with found objects and letters. She wrote about her artwork: “I worked for HUD. Thirty-five of my co-workers died in the bombing. On April 19, 1995, our world exploded. This is a tribute inside my exploded world to some of my favorite people who died in the bombing.”

The work was so powerful that OAI leadership at the time knew it needed to be seen by others. The first exhibition of Celebration of the Spirit opened at the Oklahoma State Capitol, with 10-by-10-foot photo murals of the participants lining the main entrance on the first floor, and memory sculptures, poems and journal entries displayed in the Governor’s Gallery. It stayed at the Capitol for six months before going on a tour to nine cities around the state. When the Oklahoma City National Museum and Memorial opened, the artwork from Celebration of the Spirit was included in the inaugural exhibition and is still archived there today.

“This work tells a powerful story about the ability of the creative spirit to build hope and faith in the future, and to create community,” Frates wrote in an anthology documenting both the work and the participants’ experiences, “and is of historical significance to the people of Oklahoma and to the nation.”

View the Celebration of the Spirit Anthology here